By Nasrin Sotoudeh

Source: Ms. Magazine

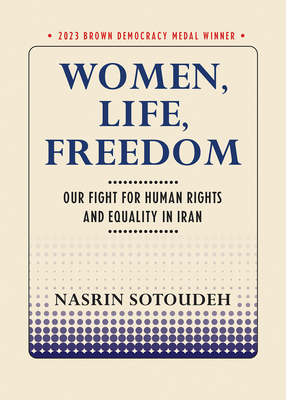

“I will try everything I can to give the women of Iran the society they deserve,” wrote human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh in her new book, Women, Life, Freedom: Our Fight for Human Rights and Equality in Iran.

Nasrin Sotoudeh is an Iranian human rights lawyer who has spent her career fighting for the rights of women and minorities in the Middle East. Arrested in June 2018 because of her work representing opposition activists, religious minorities and women who publicly protested Iran’s mandatory hijab law, Sotoudeh was sentenced to 38 years in prison and 148 lashes, on charges that included “inciting corruption and prostitution,” “disrupting public order,” “propaganda against the state” and “collusion against national security.” She had previously been imprisoned from 2010 to 2013 on similar charges—a heavy price to pay for loving one’s country.

For her important work, Sotoudeh—a long-time friend of Ms. magazine—has been honored with copious awards and designations, including the U.S. State Department’s Global Human Rights Defender title and Ms. magazine’s Top Feminist award. Just this month, she is the sole recipient of both The Civil Courage Prize, which honors individuals who show courage against evil and oppression, and the Brown Democracy Medal from the McCourtney Institute for Democracy, marking the award’s 10th year.

The excerpt below is reprinted from Sotoudeh’s forthcoming book, Women, Life, Freedom: Our Fight for Human Rights and Equality in Iran, by Nasrin Sotoudeh (translated by Parisa Saranj, foreword by Jeff Kaufman). A free download of the book is available here.

When I was 21 years old, I took an undergraduate law class in Islamic jurisprudence. The professor was a cleric who also taught at the university before the revolution and occasionally expressed opposition to the Islamic government.

I asked him, “Why does the law consider blood money (diyah) for a woman to be half of that for a man?”

This was one of the provisions in Iran’s post-revolution constitution. It meant that if a man unintentionally killed a man, he would have to pay blood money to the victim’s family—but if he unintentionally killed a woman, only half of that amount would be awarded to hers. This was obviously demeaning to women. A cleric would have the answer, I thought.

He responded with a kind of evasion, saying, “I don’t know why. Ask those who have enacted these laws.”

This was 40 years ago. While my young mind was not yet fluent with concepts like activism, civil discourse, and human rights, I was unsatisfied with my professor’s answer. Having witnessed changes in attitudes towards women since adolescence, I felt a tangled anger that I couldn’t clearly express.

The government of Ayatollah Khomeini stripped away civil and political rights. They did this with a self-righteousness that comes when a few governing men are convinced they are God’s representatives on earth.

A few years later, I decided to become a lawyer.

I started to practice law in 2003. I represented religious minorities such as Baha’is, ethnic minorities, especially Kurds, and many women and children who faced domestic abuse. I’ve also defended juveniles sentenced to death and worked with others to oppose the death penalty. I believe that human beings here, and in every country, deserve the right to freedom and dignified life.

Forty-four years ago, the Iranian people hoped for freedom in the revolution that swept away the Shah. They were lied to and betrayed. The government of Ayatollah Khomeini stripped away their civil and political rights. They did this with a self-righteousness that comes when a few governing men are convinced they are God’s representatives on earth, and their version of religion gradually slithered its way into citizens’ personal lives.

Women bore the brunt of the social and political repression. Almost all of their civil rights were taken away from them. The right to divorce, custody of their children, freedom to choose hijab, equal inheritance, and protection from polygamy—which had slightly improved under the previous regime—were completely abolished. This was despite the Islamic Republic government’s promise of a new country where men and women were equal.

Unfortunately, women lacked the political awareness to recognize the depth of the problem, and even though the new institution saw them as nothing but sex objects, they had to comprise and—ignoring the compulsory hijab law—focus on fighting for their civil rights, including the right to education and employment.

Eventually, women realized they could not claim civil rights unless they could claim control of their bodies. Thus began civil disobedience against wearing the mandatory hijab in public.

In 2006, the One Million Signature Campaign delivered a petition to the Iranian Parliament to change the discriminatory laws against women.

In 2017 and 2018, the Girls of Enghelab (Revolution) Street protests showed national opposition to this country’s compulsory hijab laws. Many were violently arrested by the morality police and security forces, and I was the lawyer for some of these women.

There is a continual demand for social justice in Iran. The Women, Life, Freedom movement began in 2021 after the arrest and brutal killing of Mahsa Amini by the morality police. The dictatorship’s response has been to tighten the noose on the Iranian people, and our women in custody and in prisons face the harshest violence. Children as young as 9 have been gunned down. Young men who survived beatings were executed.

Yet, we do not quit. We continue to pressure the government for basic rights and democratic change.

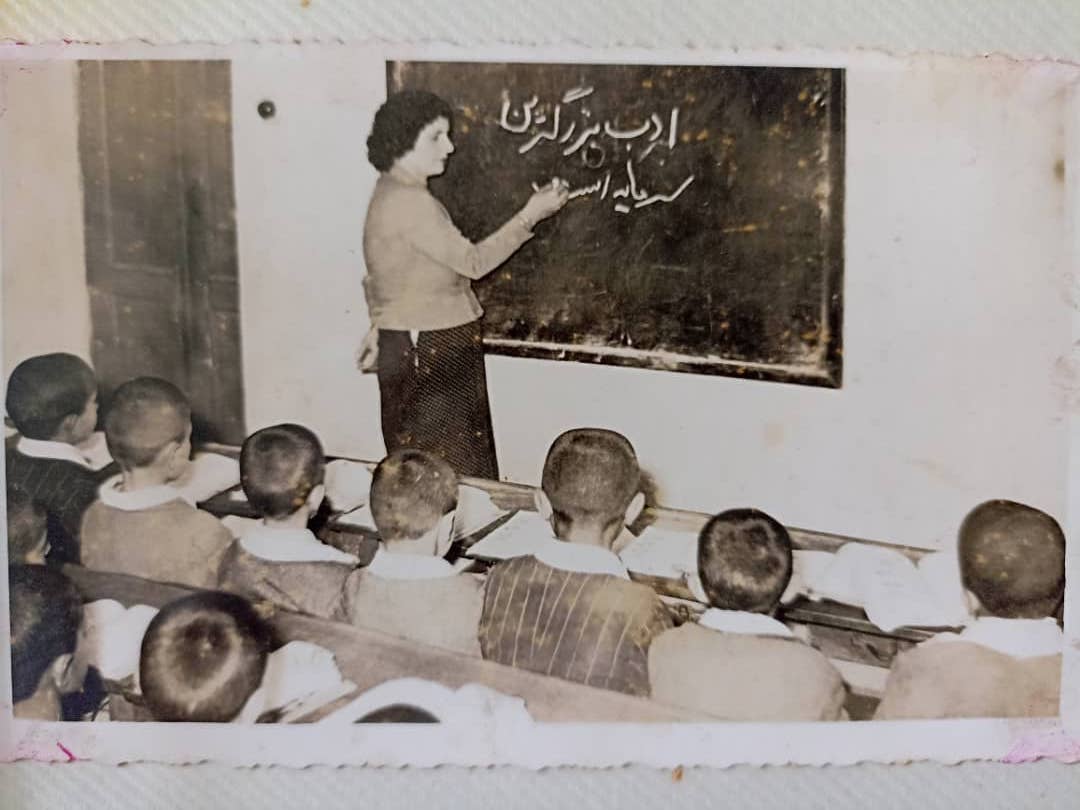

In challenging times, I like to remember my Aunt Anis. Fifty years ago, she was a teacher in a small town. Without a hijab and full of pride, she would stand in the middle of the town square and make speeches encouraging women to fight for their rights.

She loved her students, and their mothers would often go to her for personal advice. My aunt was never afraid to speak to their fathers and husbands if it could help these children in some way. One of my most vivid childhood memories is of my aunt standing up straight, hands in her pockets saying, “A woman should be able to reach her into own pockets.” She was adamant about women being financially independent. That had a profound effect on me.

This and countless other stories like hers are told all over Iran, but they are nothing but a memory today.

The reality now is the murder of Mahsa Amini, who lost her life for not covering herself in layers of clothes.

The reality is the poisoning of schoolgirls with gas for daring to get an education.

The reality is that women have endured over four decades of pain in this country.

This is, for us, a physical, bodily experience. It’s as real an aspect of life here as it could be.

Women realized they could not claim civil rights unless they could claim control of their bodies.

People far away may turn their backs on these realities, hoping they are immune. However, if the monster of oppression has nested in one corner of the world, it doesn’t mean it won’t get up and move. No, it has already begun to prowl. The monster is hungry, and it dreams of taking over the world. We must overcome our fears, stand up to the beast, and look it in the eyes.

I want our children to see and be inspired by great women like my aunt. I don’t want her to live only as a memory, as a dream. That’s why I will try everything I can to give the women of Iran the society they deserve.

Women, Life, Freedom: Our Fight for Human Rights and Equality in Iran by Nasrin Sotoudeh is published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher.