By Banafsheh Zand

Excerpted from Gutting Iran

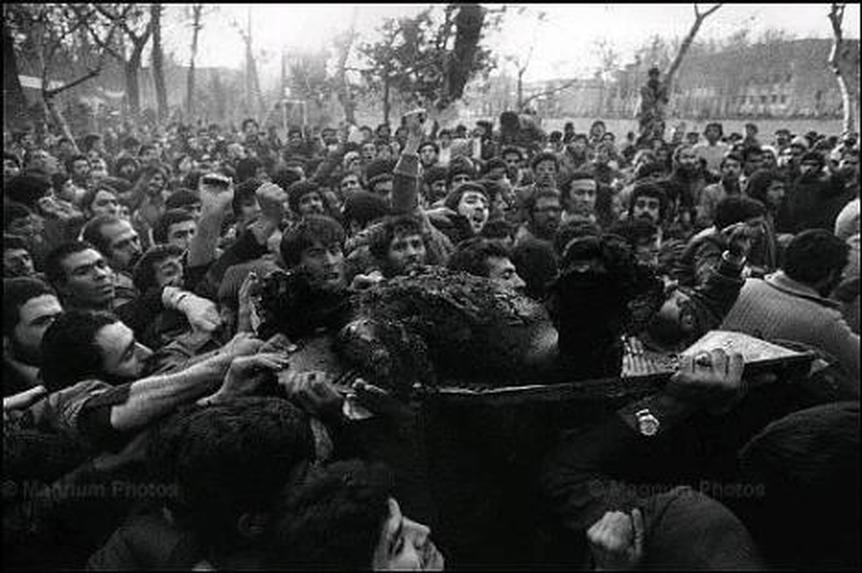

Tehran’s pre-revolution red light district, Shahr’eh No (‘New Town’ is a series of 15 photos by legendary Iranian photographer, Kaveh Golestan, photographed in Shahr’eh No from 1975-1977) was set on fire and demolished during the crazed days of the 1979 Islamic revolution. Many of the prostitutes were brutally murdered by the Khomeinists who before and after the arrival of their leader, killed indiscriminately. The prostitutes who survived those frenetic days, repented and joined the ranks of the Iranian regime in order to protect themselves from execution or punishment. The Islamic regime considers brothels to be illegal and prostitution a criminal act and depending on the gender of the person operating the brothel; it can carry a sentence of anywhere between one and ten years imprisonment.

Once Khomeini was in power, he made sure that the Family Protection Law (FPL) was repealed. The FPL, signed into law by the Shah, gave women many legal rights that disappeared once the Khomeini ruled. Now, over 35 years later, prostitutes are scattered all over Iran. Though there are no official figures, it was estimated that that in 2005, 300,000 women worked on the streets of Tehran. On Motahari Street, in the wealthy northern part of the city, the price for an hour of sex ranges from $30-80 USD.

Iran’s Shiite Oligarchy is widely known for its strict enforcement of Islamic laws, especially those regarding sexual behavior. Prostitutes in North Tehran ply their trade openly with little, if any, police interference. Punishment for prostitutes and their clients can include up to 100 lashes and jail terms. The prostitute can be executed if she is married. Nevertheless, under Iran’s judicial system, a few dollars can buy off a policeman, and what few cases are prosecuted rest on the discretion of a presiding judge. The Iranian regime has continually blamed social problems in Iran, including prostitution, on the west.

We Have No Prostitutes in Iran

Until a decade ago, the hardline regime authorities totally denied that there was prostitution in Iran. Several recent incidents have forced the authorities to admit that their policies in dealing with such social problems are not working but it is not common for Iranian officials to admit to the existence of prostitution. Usually, this type of social issue is portrayed as a Western plot to create a cultural metamorphosis in society and corrupt Iranian youth.

In March 2008, the Tehran Province police chief, General Reza Zarei, famous for his bellicose ‘morality speeches’ on the Iranian regime’s TV and one of the “architects of civil security,” was arrested in a brothel. According to one of the prostitutes, Zarei was a regular client and on the occasion of his arrest had asked six of the women to remove their clothes and stand in a row, in front of him and pray, naked.

Iran’s justice minister, Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi-Shahroudi, whose office had kept Zarei under surveillance for weeks, personally ordered the arrest. The Revolutionary Guards have, in fact, long been suspected of collecting kickbacks from Iran’s various red-light districts. Mohsen Ghazi, the case prosecutor, charged Zarei with pimping when he said that Zarei took advantage of his position and governmental privilege, abused his trusteeship and was financially corrupt.

Zarei supporters, headed by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, went out of their way to hush up the case. Even after the regime offered a confirmation, the scandal was downplayed as “minor” and “strictly private.” 84 However, given the seething animosity among the regime’s elite factions, details began to leak and reports began to appear on Iranian sites and local newspapers, until the judiciary substantiated the story.

In 2001, the judge of a revolutionary court branch of Karaj, a Tehran suburb, was sentenced to ten years in prison and a lashing for having runaway girls work as prostitutes for him. These are just a few of the instances where the Iranian regime’s own authorities were caught and held publicly accountable.

For years, women have been reporting these and many other stories about the direct involvement of the Iranian regime’s authorities who abuse their official positions and frequent prostitutes. Many women have reported, for example, that in order to have a judge approve their divorce, they have been forced to submit to having sex with the judges, most of whom are clerics. Women who are arrested for prostitution say that the arresting officer invariably demands sex from them. There are also interminable reports of police and various other regime security apparatus, tracking down young women for sex for the wealthy and powerful mullahs.

Absence of Statistics

Statistics from Iran’s Welfare and Benefits Agency show that about 400 women are arrested every year in Tehran. Nevertheless, figures from other sources indicate that the number of street women and prostitutes in the capital is on the rise and are much higher than these numbers suggest. In 2006 the head of the Sociology Association of Iran, Amanollah Gharai estimated that there were at least 200,000 street women in Tehran. At that time, it was reported that there were 6,000 plus prostitutes in prison throughout Iran, ranging in age from 12 and 25 years.During this time, several Iranian judiciary officials talked about creating a databank on prostitutes, but that idea quickly dissipated and no one ever mentioned it again.

Like many of the other Iranian officials, Tehran’s Disciplinary Police Chief, Hossein Sajedinia, has asserted that there were only a hundred or so prostitutes in Tehran. In 2011, he confidently announced that his forces could round up ‘street women’ within a week; of course, that never happened. A female member of the Islamic Parliament (Majles), Fatemeh Oliya, then challenged Sajedinia saying: “On principle we take these figures at face value, as we like to trust our police department. Hence in view of the fact that apprehending these individuals is not a difficult task, the Majles too, will offer every cooperation necessary. If the suspects have been identified, then there should be no reason for dilly-dallying.”

Unconfirmed statistics provided by low-ranking officials are often all that social scientists have to rely on. The women are referred to as “street women”, “special women” or “runaway girls”, rather than prostitutes. During a July 2012 conference in Tehran on social harms and the effects on women, research results were presented showing that the age range for prostitution in Iran had fallen and prostitution among children was on the rise. Faculty board members and a number of students from the School of Social Sciences of Tehran University, Alaameh Tabatabai University, and the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences who researched the phenomenon found that the starting age for prostitution among children is between 15 and 17 years of age.

The Director of the Social Services division of the Iranian Welfare Agency, Habibollah Masoudi-Fareed, asserted: “A number of the prostitutes take up this line of work, not only due to poverty, but also to add to their income. This should sound the alarm bell for Iran’s society. Based on statistics from the rehabilitation centers of the welfare agency, ten to twelve % of the street women are married and during the last eight years, their median age range is between 20 and 29. Of course the statistics of our organization’s rehabilitation centers differs from social statistics.”

When Masoudi-Fareed’s comments were published in one of the Iranian regime’s affiliate sites—the Iranian Student News Agency—became so problematic for the editors that within a few hours of the information’s publication the title was changed and the names of the cities listed with the highest prevalence of prostitution deleted. Publishing these statistics angered the regime officials so much that they scrambled to deny the entire issue, which Masoudi-Fareed’s boss (the Director of the Iranian Welfare Agency), Homayoun Hashemi, to call her “just an employee” whose stats were unreliable. He said, “Certain statistics have no positive function in society; instead, they have a negative psychological impact. It is better not to talk about them.” However, none of this stopped the news from spreading and further research was conducted showing that less than 14 is the real age of entry into prostitution.

Observers emphasize the fact that many of the married prostitutes work with their husband’s full knowledge. This suggests that unemployment and poverty is an issue that both men and women face. In a recent Tehran study, changes in the tenor of the work has changed. In the 1980s and 1990s the age for prostitution was over 30, but since the year 2000 it has fallen to age 15.

If previously prostitution was a way to earn money for primary needs, now it is for secondary needs as well. Before, prostitution was taken up by single women who had a very low standard of education, and now it is taken up by married, educated women who are driven to it out of necessity. Presently, with the surge in the age of marriage and the decline of the age of maturity, the difference between maturity and marriage has fallen to between 15 and 20; however, in responding to these problems, officials and religious leaders have refused to offer any perspective on sexual issues.

The Prostitutes Themselves

Most stories of prostitutes involve poverty, drug addiction, and abusive families; often all of those go hand in hand. Like other parts of the world, prostitutes on the streets of Tehran, haggle with potential clients before they escort the ‘Johns’ (or “Mohammads’ in their case); believing that the price was settled and that they will be paid after their ‘business’ is completed. The prostitutes are often cheated or short-changed, and the whole situation more often than not, ends up in a loud confrontation. This scenario is regularly recounted by most prostitutes in Iran.

Of course, there is always temporary marriage, or Nekaah Monghata (also known as Seegheh), 99 a rather convenient covenant in Shiite Islam. Seegheh marriages, can last anywhere between the duration of intercourse, to a lifetime, and is something to which many women submit, in order to have financial support as frequently, women do receive money for entering into the contract. This is especially true of widows with children who have no other means of survival. By reciting a couple verse from the Quran, the deed is done and the verbal contract, which does not need to be registered, can be recited by anyone.

As an example, this is a flyer of an ‘agency’ that organizes such marriages in the holy city of Mash’had which is home to Shrine of the eighth Imam, Imam Reza, and where Shiite pilgrims travel for blessings.

In the 2002, The New York Times author, Nazila Fathi, wrote about a woman named ‘Susan’. Susan was forced into prostitution at age 16 by her husband, who used the money she earned to feed his drug habit. At age 26, she left her abusive addicted husband and had no other means of support herself and her ten-year-old son, for whom she is the only breadwinner. In 2013, almost exactly eleven years later, Brendan Daly conducts another interview with another prostitute in Tehran, for The Washington Times. Though there is a ten-year and gap between the two interviews, not much has changed in the stories each woman tells; in fact, things are actually said to be much worse.

Parisa, which is a pseudonym, on the other hand is from a lower middle-class family from central Iran, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Information Technology. She is 23 and despite her degree, she is driven to prostitution. She has lost her job, which paid exceedingly low wages for someone with her qualification. She circulates in the affluent areas of uptown Tehran and there she is able to make the $80 USD per client. When she was ‘gainfully’ employed in her vocational field, $80 was three-fifths of her monthly income at a mid-size tech firm.

Parisa is far from alone in this unfortunate trend; like many other young women in her circumstances, she cannot be dependent on her family, who lives in another part of Iran, and must do what it takes to survive the economic conditions created in Iran by the government. She knows she can become a seegheh (temporarily married) so that she is legally protected from the police—or perverts as she puts it; but so far, she has not bothered to do it. “No one cares about such things anymore, not in Tehran anyway,” she says, laughing. “The police don’t care. The mullahs don’t care. And definitely the young guys who pay me for my time don’t care about their religion.”

Parisa’s wealthy, male neighbor criticizes: “Our girls are selling themselves on the streets! You never saw this five or six years ago, and all Khamenei can talk about is the nuclear program. What nuclear program? Some Russian-built antique that’s been sitting there doing nothing for 30 years?”

‘Cyber’ Prostitution

In 2012 news of cyber prostitution and internet sex also got out. The site, which describes itself as independent and unaffiliated with any Iranian political faction, boasts an advisory board and contributing editors, all of whom are in the Iranian regime’s elite echelons. The article, penned by contributing editor to the site’s social section, Seyyed Mohammad-Hossein Hashemi, a documentary filmmaker close to the regime, offers an unequivocal brief on the rise of this hi tech by-product of the ‘trade’.

Many prostitutes use cyberspace mainly to find customers and avoid the possible risks that women on the streets might face. Using platforms like Facebook and Yahoo! Messenger provide them with protection and enables them to have loyal customers. They create a user identification to enter chat rooms. Statistics show that their 55% of their customers are between the ages of 16 to 25 and 45% over 25. They engaged in video activity after they’ve introduced themselves, give their age, and taken users credit card numbers; two thousand Tomans ($80 US) for ten and five thousand Tomans for thirty minutes, on camera.

‘Mahsa’ is a 21-year-old girl has been in the business for six months. Her customers have no idea where she lives and her family knows nothing of her work. When she is asked to meet her customers in person, she agrees but charges more—between 25-80 thousand Tomans for an hour, and 90 to 300 thousand for the night. Mahsa also puts her internet colleagues—who are all different ages—in touch with new clients. She has a Facebook page with photos and her friends’ contact information, though she does not accept friend requests without charging two thousand Tomans for it. Then forty-eight hours later—and after the charge has cleared—she phones the client and provides her name and meeting place. Some of the women offer HIV/AIDS tests while others refuse.

Back in 2000, a small number of government departments suggested legalizing brothels under the name of “chastity houses” (khaaneh’yeh afaaf) as a way of bringing prostitution under control. The floated plan involved using security forces, the judiciary, and religious leaders to administer guesthouses where couples would be brought together in a safe and healthy environment.

Many politicians, clerics, and women’s groups denounced the reported proposal followed by government denial that such a plan was in the works. Nevertheless, the vigorous debate focused new attention to the scale of prostitution in Iran’s capital and the government’s eagerness to find a solution. Habibollah Masoudi-Fareed suggested: “The Social Welfare Agency must take a more active position approach towards women and sexual workers. Many need to receive help and contraceptives, from the organization; however, because prostitution is considered a punishable offense, they do not call on the organization to ask for help.”

He has also said that policy makers in Iran are reluctant to provide even the minimum funding needed to help prostitutes leave the profession because, “they wrongly assume that prostitutes are to blame for the problems they face.”

Despite the acknowledgement of the problem, there seems to be no single government agency responsible for addressing the issue of prostitution. The spokesperson of Majles’ social committee a few months ago had said that: “In the course of examining the issue of street women in this committee, the Wellbeing Organization announced that it would not accept the women the police had rounded up, adding that even if it did, it had the capacity to only keep twenty to twenty-five of them during a year.”

The Wellbeing Organization facilities for the larger Tehran area currently has the capacity to keep a maximum of fifty street women, while the police round up between 300-400 prostitutes every year; these women are sent to the Wellbeing Organization by court order. This is the same across the country, as there are only twenty-three such centers in Iran. While discussing this problem, an Iranian official said that runaway girls could not be kept at government facilities because they have not committed any crimes. Tehran’s police chief alluded to this problem when he said last year that rounding up these women involved going in a vicious circle, with no results. When the head of the Majles social committee was asked two years ago to present a plan to address the issues of prostitutes and street women, she said, “Our society has so many problems and issues that our top priority is unemployment and jobs for the youth, including other even more important issues.”

As Nazila Fathi writes in her 2002, NY Times article, at one time the idea of “chastity houses” was floated by various figures within the Iranian regime: “One of the few religious leaders to speak out in favor of ‘chastity houses’ is Ayatollah Muhammad Moussavi Bojnourdi. Temporary marriage has been publicly approved since early 1990s by Iranian officials, particularly Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was president then, as a way to channel young people’s sexual urges under the strict sexual segregation of the Islamic republic. ‘I would not have supported chastity houses had it not been for the urgency of the situation in our society,’ he was quoted as saying in the newspaper Etemad. ‘If we want to be realistic and clear the city of such women, we must use the path that Islam offers us.’”

However, women’s rights advocates object to the concept of ‘chastity houses,’ saying that, “Temporary marriage should be used only for certain cases. It should not be promoted as a way to resolve such social problems” as prostitution.References:

1. Wikipedia contributors, “Iran’s Family Protection Law,” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia, April 15, 2014, version ID: 604303211, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran’s_Family_Protection_Law

2. Golnaz Esfandiari, “Iran: Prize-Winning Documentary Exposes Hidden Side of Society,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFERL), March 25, 2005, http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1058130.html

3. Parto Parvin, Arash Ahmadi, “Iran sets sights on tackling prostitution,” BBC News Middle East, July 26, 2012, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18966982

4. “A Police Chief Incarcerated: Prostitute Scandal Rattles Tehran Government,” Spiegel Online International, April 28, 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/a-police-chief-incarcerated-prostitute-scandal-rattles-tehran-government-a-550156.html

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Nazila Fathi, “To Regulate Prostitution, Iran Ponders Brothels,” The New York Times, August 28, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/28/international/middleeast/28IRAN.html

8. Donna M. Hughes, “The Iranian Sex Trade,” Women Freedom Forum, June 14, 2010, http://womenfreedomforum.com/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=596

9.رییس انجمن جامعه شناسی ایران خبر داد: کاهش سن روسپیگری در ایران, Kayvan Bozorgmehr, “Drop in Prostitution Age in Iran,” RoozOnline, June 14, 2011, http://www.roozonline.com/persian/news/newsitem/article/-24d229d1b5.html

10.Ibid.

11.Ibid.

12.رئیس پلیس: تهران فقط ١٠٠ زن خیابانی دارد, گردنبند برای آقایان ممنوع, Kaveh Ghoraishi, “Tehran Police Chief: There are only 100 street women in Tehran, collaring men is prohibited,” RoozOnline, June 7, 2011, http://www.roozonline.com/persian/archive/archivenews/news/archive/2011/june/07/article/-42ea99efa3.html

13.Ibid.

14.ایران اسلامی؛ تن فروشی در سنین کودکی, “Islamic Iran: Child Prostitution,” Iran Press News, April 17, 2012, http://www.iranpressnews.com/source/121239.htm

15.Ibid.

16.روسپیگری- از فقرتئوری تا فقر زنان, Ali Tayefi, “Prostitution – from theoretic poverty to poverty in women,” Radio Zamaneh, March 19, 2013, http://www.radiozamaneh.com/1319

17.Ibid.

18.Ibid.

19.Ibid.

20.Ibid.

21.Fazel Hawramy, “Discrimination in Iran’s marriage law goes unchecked,” The Guardian, Iran Blog, March 6, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2012/mar/06/iran-temporary-marriage-law-sigheh

22.مژده، مژده، سرانجام صیغه خانه بارگاه قدس رضوی گشایش یافت, Sohrab Arzhang, “Good news, finally homes for temporary marriage opens at the holy shrine,” Fozoole Mahaleh website, September 30, 2010, http://bit.ly/1uvzbot

23.Nazila Fathi, “To Regulate Prostitution, Iran Ponders Brothels,” The New York Times, August 28, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/28/international/middleeast/28IRAN.html

24.Brendan Daly, “Iran’s educated, middle-class and part-time prostitute,” The Washington Times, May 16, 2013, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/may/16/irans-educated-middle-class-and-part-time-prostitu/?page=all

25.Ibid.

26.Ibid.

27.Ibid.

28.آنها تن میفروشند؛ تنها با یک کارت شارژ, “They sell their bodies, with just one charge card,” Parsineh Website, April 9, 2012, http://bit.ly/1rmNrvW

29.Ibid.

30.Ibid.

31.Ibid.

32.Nazila Fathi, “To Regulate Prostitution, Iran Ponders Brothels,” The New York Times, August 28, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/28/international/middleeast/28IRAN.html

33.روسپیگری- از فقرتئوری تا فقر زنان, Ali Tayefi, “Prostitution – from theoretic poverty to poverty in women,” Radio Zamaneh, March 19, 2013, http://www.radiozamaneh.com/1319

34.Ibid.

35.رییس انجمن جامعه شناسی ایران خبر داد: کاهش سن روسپیگری در ایران, Kayvan Bozorgmehr, “Drop in Prostitution Age in Iran,” RoozOnline, June 14, 2011, http://www.roozonline.com/persian/news/newsitem/article/-24d229d1b5.html

36.Ibid.

37.Nazila Fathi, “To Regulate Prostitution, Iran Ponders Brothels,” The New York Times, August 28, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/28/international/middleeast/28IRAN.html

38.Fazel Hawramy, “Discrimination in Iran’s marriage law goes unchecked,” The Guardian, Iran Blog, March 6, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2012/mar/06/iran-temporary-marriage-law-sigheh