Source: Hengaw

Security situation on the anniversary of Armita Garavand’s extrajudicial killing

On the first anniversary of Armita Garavand’s state-sanctioned killing, security forces of Iran have imposed strict measures to silence her commemoration, pressuring her family against sharing any content related to her on social media. Starting Saturday morning, October 27, security forces were stationed around Armita’s grave and family home, prohibiting any commemorative events. The family was even restricted from sharing an image of a flower wreath placed in her memory on social media.

According to evidence obtained by Hengaw, security forces replaced Armita’s gravestone photo just prior to the anniversary, allowing only her immediate family to visit her grave for a brief 15 minutes. The original photo on her grave, a selfie chosen by the Garavand’s family, depicted her without the mandatory hijab. However, recent images show that authorities removed this image and replaced it with a digitally generated version of her in a hijab.

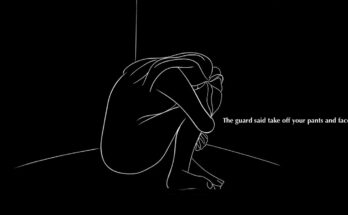

Armita Garavand, a 17-year-old student from Kermanshah residing in Tehran, suffered fatal violence at the hands of Iran’s “morality patrol” a year ago for not wearing the hijab at Tehran’s “Shohada Square” metro station. Following the incident, officials stated she had “fallen into a coma,” an account contradicted by witnesses and human rights organizations.

The connection between Armita Garavand’s extrajudicial killing and the “Woman, Life, Freedom” Movement

The government-sanctioned killing of Armita Garavand echoes the tragic death of Jina (Mahsa) Amini and remains a stark reminder of the ongoing “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom) movement. Recent information obtained by Hengaw highlights a connection between Armita’s death and the struggle against mandatory hijab laws—a connection that underscores how her defiance of these restrictions.

According to Hengaw’s sources, Armita, like many in her generation, openly opposed Iran’s compulsory hijab mandate. She frequently engaged in verbal confrontations with local clerics and appeared in public without the mandatory hijab. In one account, she responded to a cleric’s insistence on hijab by saying, “I’ll adopt your version of hijab the day you remove your turban.” This act of defiance was seen as aligned with the values championed by the “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” movement.

Hengaw has also confirmed that Armita’s family has refrained from filing any official complaints about her death, a decision reportedly made under intense pressure from security forces. These forces have imposed extensive surveillance on the Garavand family, closely managing any information surrounding Armita’s death and discouraging public discussions about the incident.

On commemoration of Armita Garavand’s extrajudicial killing, Hengaw offers this report to shed light on her involvement in the movement, the oppressive aftermath her family has faced, and the controlled media narrative intended to quell any public outcry over her death due to hijab enforcement policies.

28 Days in a Coma and Security Pressure on Armita Garavand’s Family

From the moment of Armita Garavand’s assault and her subsequent transfer to Fajr Military Hospital, security agencies moved swiftly to control the narrative on social media. Independent journalists were barred from accessing her family and medical team, with strict restrictions on reporting from inside the hospital. The intensive care unit was placed under heavy surveillance, and all visitations were strictly limited. Maryam Lotfi, a journalist from Shargh newspaper, faced detention after a phone call with Armita’s mother, while access to the hospital’s ICU was entirely sealed off.

In the early days following the incident, Armita’s parents appeared on camera in what seemed to be a coerced statement. Nervous and hesitant, they relayed a pre-determined explanation: that her condition was due to “low blood pressure” and that she had “hit her head on the train.” Armita’s mother, Shirin Ahmadi, appeared visibly unsettled, stating, “I don’t really know… they said her blood pressure dropped or something like that.” This staged interview was presented to viewers as a forced statement.

Around the same time, another interview surfaced showing Armita’s father, Bahman Garavand, saying, “I haven’t seen her for a few days… I’m at work; I just know she’s in a coma.” Despite his daughter’s condition, he was forced to continue his daily labor, while her mother stayed at the hospital.

Throughout Armita’s coma, Hengaw’s sources reveal that her family’s access to her was tightly restricted and monitored. Her sister wasn’t even permitted to see Armita through a glass partition. This complete security lockdown lasted for the full 28 days of her coma.

During this time, the family and her friends faced repeated interrogations, including detentions lasting up to five hours. This interrogation happened in October 1, 2023. Friends of Armita were also coerced into providing forced confessions on television. One of Armita’s close friends and classmates, whose identity remains protected, suffered a heart attack from the trauma and now battles severe psychological distress.

In the days after Armita fell into a coma, a video surfaced showing her taking the daily route to school, raising questions about its authenticity, especially given the uncertainty surrounding the events of that specific day. Additionally, none of the morality officers reported to be present at their posts after the incident.

28 days in coma and state-controlled media manipulation

The Iranian state never released footage from inside the metro related to Armita Garavand’s case. At the time, journalist Ameneh Sadat Zabihpour commented, “I asked why no footage from inside the train was released. Series 100 trains don’t have cameras.” However, it seemed implausible that the exact train Armita boarded would lack cameras. Contrary to Zabihpour’s misleading statement—her interrogative journalism had previously been exposed by political prisoner Sepideh Gholian—an analysis of external footage confirmed that Armita had been on a Series 1200 train, not a Series 100.

Following a detailed examination of videos released by security agencies, Hengaw determined that these videos were heavily manipulated, with numerous inconsistencies. For instance, in the footage provided, a segment from 6:52:40 to 6:54:20 (100 seconds) is missing. Similarly, from 6:54:50 in the supermarket to 6:57:31 (150 seconds) was cut, as well as from 6:58:15 to 6:59:40. Multiple reviews revealed other discrepancies: in one scene, where Armita walks past the gate, a woman initially ahead of her appears behind her in footage from a different angle. In another instance, three men on the escalator disappear when the view shifts to another camera. Such inconsistencies raise serious doubts about the authenticity of the footage that purportedly documents Armita’s entrance to the metro.

Hengaw’s investigation at the time revealed, from specifications on Tehran Metro’s official website, that all metro trains from 2011 onward were equipped with cameras, directly contradicting claims by security forces. The specifications confirming this were promptly removed from the website.

Additionally, Hengaw reported that, according to a statement by the Coordinating Council of Cultural Associations, the head of Security for the Ministry of Education—accompanied by a security team—visited Armita’s school, Arvato al-Wathiqa. The team reportedly threatened her classmates, warning them not to share information about Armita, while teachers were told they would be “dismissed” if they disobeyed security instructions.

Two of Armita’s friends were interviewed during this time, shown in the same location, looking away from the camera, and using identical phrases like “head injury between the train door and platform,” with visible signs of distress. This setup is typical of coerced confessions managed by security agencies. On October 4, 2024, IRNA released footage of these two individuals, identified as Mehla and Fatemeh, with their faces blurred, in coordination with Zabihpour’s security report. Hengaw emphasizes that Mehla and Fatemeh are not the actual names of Armita’s classmates, who were compelled to make forced confessions.

The government subsequently released surveillance footage tracking Armita’s movements from outside to inside the metro, but this only intensified public skepticism. Careful observation shows Armita appearing well and in good spirits as she enters the metro and shops at a supermarket. She does not look like someone who would lose consciousness within minutes, as state media later claimed. Footage shows her feet moving shortly after the incident, contradicting government reports that she was already unconscious. Forensic analysis by Amnesty International revealed digital alterations in the CCTV footage, identifying these manipulations as part of a disturbing attempt by Iranian officials to conceal the truth.

In an audio file released by state media regarding the incident, a metro employee is heard calling emergency services. At the 16-second mark, the employee states, “A female passenger was about to board the train but is now on the ground.” The section of the call describing what happened inside the train was omitted.

Throughout Armita Garavand’s coma, Hengaw consistently followed and reported updates, while her family was subjected to extreme security measures, particularly as she was hospitalized in a military hospital with high security. Security forces instructed her family not to communicate with foreign media or human rights organizations, particularly Kurdish media, implying that any such contact would be perceived as separatist activity. Security personnel even warned the family, “These people plan to kill you; we (security forces) are protecting you.”

Hengaw has also learned that a man named Saeed Garavand, a police colonel in Tehran and Armita’s uncle, played a central role in censoring information during her hospitalization. He reportedly confiscated phones from several family members and monitored their online activity, even threatening them with detention.

Security pressures on Armita’s family included surveillance of their communications, monitoring their home and hospital environment, and the detention of Armita’s mother, Shahin Ahmadi. According to Hengaw’s findings, these security measures aimed to isolate the family from social and political networks in Kurdistan, allowing only selective and vague information about Armita’s condition to be released through state media. The coerced confessions, emphasis on securing the hospital environment, restrictions on journalists, and pressures on Armita’s family and classmates all reflect a coordinated media manipulation strategy aimed at controlling public reaction to her extrajudicial death.

Confirmed death of Armita Garavand and security surrounding the burial

On October 28, 2023, the Tasnim News Agency, affiliated with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, officially confirmed the death of Armita Garavand. A close family member informed Hengaw that they believe Armita was killed immediately following her assault, with news of her death withheld for 28 days under a coma narrative, possibly to mitigate public outrage and intensify security measures around the family.

Documents obtained by the Hengaw Organization for Human Rights show that, following the announcement of Armita Garavand’s confirmed death and her burial, numerous individuals were detained, with Hengaw verifying the identities of 22 of them. Among these, 22 individuals — identified as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Manzar Zarabi, Masoud Zeinalzadeh, Mohammad Garavand, Fatemeh Haqani, Niloufar Mirzaei, Hamid Abbaspour, Hashem Mehr Alian, Majid Houshang Kianpour, Mohammadreza Fakhim Avar, Mehran Haji Hashemi, Asghar Seyed Faraji, Ali Sokhteh Ra, Ramtin Bandeh, Fatima Zahraei, Mitra Ghasemi, Yousef Houshyar, Siamak Masihpour, and Iman Miri — were arrested at the funeral. Two additional people, Hamid Hemmati and Ramin Velinejad from Ilam, were detained due to their protests on social media regarding Armita’s violent death. Additionally, Sediqeh Vathmeqi and several women’s rights activists present at the burial were reportedly assaulted by security forces.

Hengaw further reports that, despite repeated requests from Armita Garavand’s family to return her body to Kermanshah, this was blocked by security forces, who expressed concerns that “this incident could resemble the case of Jina Amini.” A source from Hengaw reported that security officials directly informed the Garavand family, stating, “Due to Kermanshah’s border location, we cannot handle a recurrence of the unrest seen at Mahsa’s funeral.”

Hengaw’s year-long monitoring of the Garavand family’s security situation revealed that, in addition to being denied permission to return Armita’s body to Kermanshah, the family was also prohibited from holding traditional memorial services on the seventh and fortieth days in the city.

Further findings from Hengaw reveal that the family faced considerable restrictions regarding Armita’s headstone, including limitations on inscriptions. The family was not permitted to engrave Armita’s favorite Kurdish poem—one she had lip-synced in a video during her lifetime—on her grave marker. Security officials also objected to including her mother’s name on the headstone; however, after persistent efforts, especially from her mother, it was eventually allowed. The family’s choice of photo for Armita’s grave was also altered multiple times. In the end, without the family’s consent, an AI-generated image of Armita wearing a mandatory hijab was placed on her headstone by security agencies.

Hengaw recognizes Armita Garavand’s death as a government femicide, a part of systemic gender-based oppression. Such cases, involving targeted violence against women under enforced gender policies like mandatory hijab laws, fall under government-sanctioned femicides when perpetrated or enabled by police and security agencies.