Homa Hoodfar, who spent 121 days in an Iranian jail for ‘dabbling in feminism and security matters’, says the world must not ignore the social and legal inequalities women continue to face

Source: The Independent

By Homa Hoodfar

On International Women’s Day last year – 8 March 2016 – I walked the streets of Tehran by walking in the streets, riding the Metro to attend a discussion group and reading some Happy Women’s Day greetings on social media. In my heart and mind, I celebrated these Iranian women in the women-only train compartments in their colourful outfits and loose scarves, resisting the regime’s attempt to control their bodies and eliminate their choices.

I celebrated their incredible entrepreneurship, which has turned the women’s sections of the busy Tehran Metro into platforms for public discussion on matters that concern them and a shopping mecca full of women from all walks of life, shopping for an incredible variety of goods despite ongoing pressure from the authorities to shut down their informal and innovative methods of boarding and exiting the trains to sell their kitchen equipment, clothing, makeup, sports gear and other goods.

On a high note, I went to sleep that night feeling optimistic as I prepared to leave Iran two days later. But on the following evening, as I was packing, my apartment was raided by Revolutionary Guards. I was eventually arrested and ultimately sent to Evin prison, charged with “dabbling in feminism and security matters” – a crime that does not actually exist.

Knowing that my incarceration was just one tiny incident amid a huge history of women’s struggles helped keep my spirits up for the 121 days I was in prison. So did the songs that played in my head: The feminist anthem of my youth, “Bread and Roses”, and the Iranian song “Zan” (Woman) by Ziba Shirazi, telling Ayatollah Khomeini that women are softer than flower petals and stronger than iron, do not try to veil us, reminding him that he and all other men owe their very existences to women.

Unified global voices

As we remember the struggles that have brought us closer towards gender equality, we also must consider the social and legal inequalities women continue to face worldwide. While women’s quests for gender equality, dignity and justice are arguably universal, strategies and solutions vary widely under a vast range of social, cultural and political conditions and constraints. Not recognising this multiplicity has undermined feminist solidarity and has prevented a diversity of strategic solutions.

As an Iranian woman, I well know the fragility of gains women have made. I recall my pain and frustration in the weeks following the 1979 revolution, when Ayatollah Khomeini and others in charge passed sharia laws in conjunction with practices straight out of the Middle Ages, and rendered Iranian women second-class citizens. In Pakistan, President Zia ul-Haq soon followed Khomeini’s lead.

These developments encouraged Algerian Islamists who kidnapped and sexually enslaved women throughout the 1980s. They harassed unveiled women, and women working and studying outside the home. A similar story unfolded in Sudan. In Afghanistan, beginning in 1994, the Taliban, once considered US allies and championed as freedom fighters by western media, took the oppression of women to new levels.

Throughout the 1980s, Amnesty International – then the most prominent of human rights’ organisations – refused to campaign for jailed and tortured gender activists, insisting they were not political activists and so outside their mandate. Amnesty also refused to condemn governments that ignored non-state actors’ violations against women. Among feminists and within women’s organisations, frustration and disappointment with Amnesty deepened.

This disappointment, spurred the emergence of a truly transnational women’s movement. At that time, I could not imagine Amnesty would one day take the lead in campaigning to free me from Iran’s Evin prison 25 years later.

But that was during the 1990s, and well before Amnesty’s change in mandate. The internet and social media, and even affordable international telephone connections and fax machines, were not yet a reality.

Determined to establish women’s rights as human rights through the development of global legal tools and political and social structures, women formed networks such as Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (Dawn),Women Living Under Muslim Laws and the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights.

Advocates of all ages, nationalities, religions, gender orientation and political affiliations mobilised to research, and collected thousands of testimonies of violence against women: Second World War rape survivors; German women raped by Russian soldiers; Korean women used as sexual slaves for Japanese military personnel; Bangladeshi women raped during the 10-month Liberation War of 1971; Bosnian women raped as part of the “ethnic cleansing strategies”.

The data was presented at regional meetings, national and international tribunals and finally at the UN Human Rights Committee in June 1993 that established women’s rights are human rights with the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. The global demand for gender equity and justice is also reflected in the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action signed by UN members at the 1995 Women’s Conference in Beijing.

These declarations provided women around the world a framework for working towards gender justice and for holding their national governments accountable in the process. But even though change continues to ripple, the full achievement of the goals laid out 30 years ago are far from realised.

The North America-based #MeToo and #TimesUp movements are among many ongoing fights against the commodification and victimisation of women as sexual objects and the gendered power differentials that persist in ways that gravely constrain the lives of girls and women everywhere.

Though it may seem obvious to younger generations, the ideas of “women’s rights as human rights” is only 25 years old, and is still frighteningly tenuous in many contexts.

1979: Imposition of the hijab

As an Iranian, this is not a hypothetical issue for me. In 1979, I saw how easily the limited reforms and modest gains that Iranian women had previously struggled for were annulled within two weeks of the end of the revolution. As post-revolution generations of Iranians have learned, without protection and nurturing, rights perish.

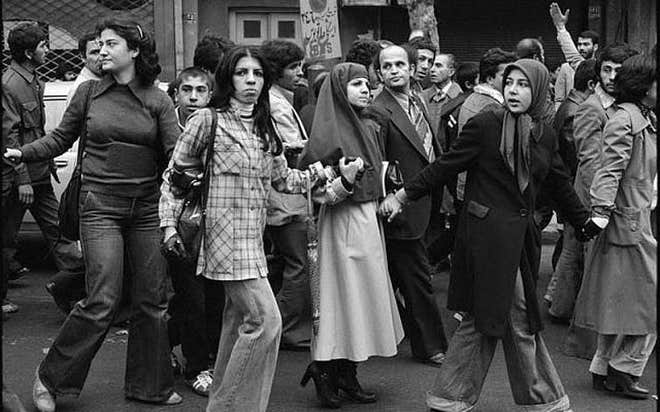

In the early days of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), leaders decided that women would collectively symbolise the Islamicisation of the nation to Iranians and the world. On 7 March 1979, the IRI imposed a compulsory hijab for women. The next morning, thousands of women all across the country poured into city streets to protest compulsory veiling.

The vociferous opposition took the new leaders by surprise and they temporarily retreated. Over the next two years, however, the regime used the rhetoric of patriotism to gradually reimpose veiling, first for government employees, then for any woman accessing government offices and buildings, then for students.

Ultimately, public veiling was imposed for all females, Muslims or not, over the age of nine. The state claimed that unveiled women caused men’s immoral thoughts – a persistent trope in the history of female diminishment and male impunity.

Extreme political suppression in the early years of the IRI and the bloody and costly Iran-Iraq war (1981-88) made organised, collective action for women’s rights impossible. Yet various strategies for resistance continued. For example, many women refused to wear the all-enveloping black chador (literally tent) favoured by some conservative groups and promoted by the Republic, arguing that the black chador did not exist at the time of the Prophet.

Instead, they wore scarves and “manteaux”. They challenged the government’s colour restriction as well, (brown, white, navy blue and grey), arguing that even the most conservative interpretation of Islamic text fails to even hint at colour restrictions, and that the Prophet’s favourite colour was pink.

In those early years, many women, myself included during my visits, wore the very bright and shiny colour known as Saudi green, which annoyed the regime to no end, but which the morality police were at a loss to address since green is generally considered the colour of Islam. Within a few years, women started to appear in public in other bright colours.

The hijab was also intended by the regime to demonstrate national pride in opposition to the alleged Western hedonism of fashion popularised by the previous government. Iranian women continued to subvert the regime’s intentions by styling “traditional” attire in new ways, donning bright-coloured ethnic patterns that nevertheless completely conformed to Islamic codes of modesty.

Thus the morality police and other state agents had no easy justification for arresting women for dress-code violations, and tactics for expressing agency and opposition by this first generation of women living under the IRI continued.

Daughters of the revolution

Over time, among many demographics, successive generations of girls born and raised in the IRI have worn increasingly shorter and tighter tunics over their leggings; their scarves have become ever smaller and looser. Older women, claiming as a result of age to no longer be seductive, have allowed their head coverings to slip lower as they moved through their cities and towns going about daily business.

Despite the state’s investment of massive resources to employ hundreds of thousands of paid and volunteer morality police, and almost 40 years of school curricula designed to inculcate “Islamic” values as defined by the regime, the regime has not accomplished its goals.

The world has been surprised recently by a new wave of women’s activism in Iran. Bareheaded Iranian women climb on platforms and benches in public spaces, white scarves tied to the ends of poles, waving their hijab flags to protest compulsory veiling.

Alone and silent, the women can hardly be charged with mobilising against the state or disturbing the peace – the usual justifications for arresting demonstrators. While some have been arrested for baring their heads in public, often the authorities are generally looking away to avoid escalating tension, drawing attention to the women and fuelling the movement.

But videos and images of these actions are shared widely on social media, bringing a new sense of empowerment to women in Iran and drawing increasing interest from media elsewhere.

The young protesters are being called “daughters of the revolution”. The movement has taken the regime by surprise – there has been no coherent response and the number of women making flags of their headscarves in public spaces is increasing. There is no organised, central orchestration of these actions, though they have attracted many supporters.

Rather, we see an organic civil movement manifesting the widespread dissatisfaction of large segments of both the male and female population, including many women who will wear the veil regardless but object to the compulsory hijab.

There has been at least one instance of a woman in full chador climbing onto a platform on a busy street and waving a scarf to protest her lack of bodily autonomy. The struggle is not about a piece of cloth on a woman’s head, it is about the gender politics that cloth symbolises, and its use to silently and broadly communicate a rejection of state control over women’s bodies.

The political aspect of the struggle over the veil can be perplexing to outsiders, who wonder why some groups of women in Turkey and Europe fight for the right to wear the veil while in Iran many women – including some devout women – have fought for almost four decades for the right to remove their veils. In all cases, women are demanding state recognition of bodily autonomy as an essential step to recognition of their full personhood and citizenry rights.

And so I will continue to both protest and celebrate on International Women’s Day. We need this day of conscious connection to the long, sometimes violent history of women’s struggles for personhood; a day to reflect on the rights we have gained; and a day to recognise the vigilance required to retain those rights – rights women of many nations and contexts have yet to achieve. This I know from personal experience.

Homa Hoodfar is a professor of anthropology, emerita, at Concordia University. This article was first published in The Conversation (theconversation.com)